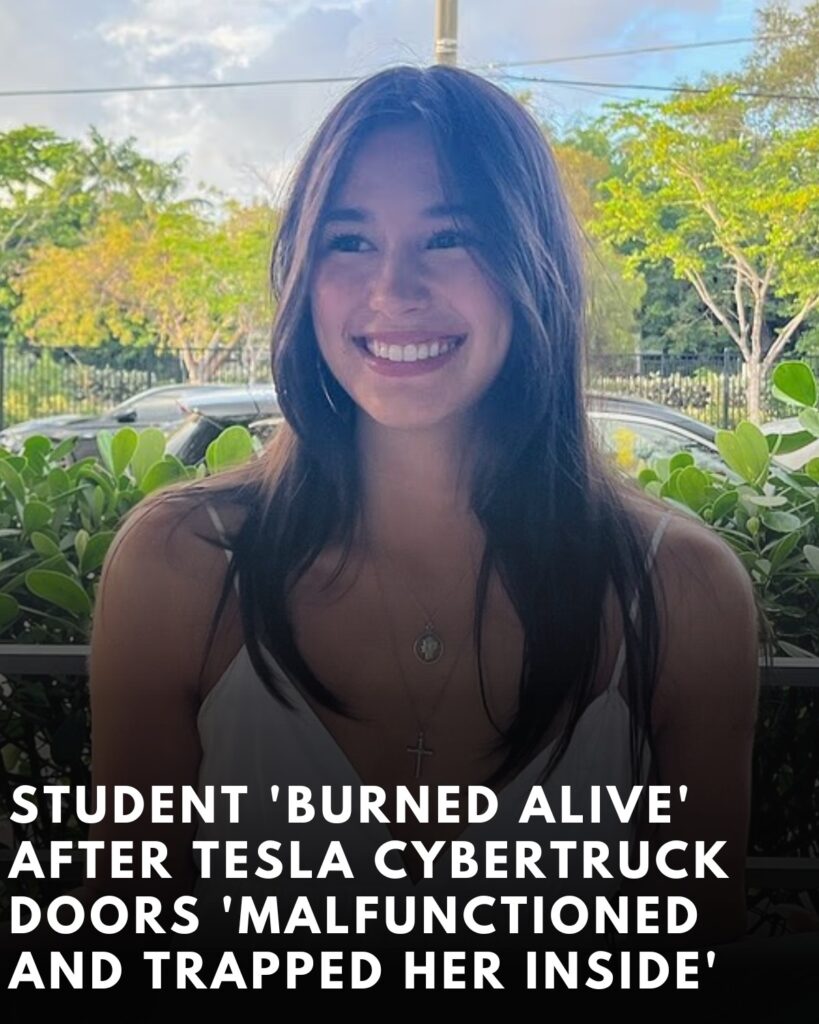

The parents of two college students killed in a late-night Tesla Cybertruck crash in Piedmont, California, have filed wrongful-death lawsuits alleging the pickup’s electronic door system failed after impact, trapping their children as the vehicle burned and filled with smoke. Court filings in Alameda County detail claims that 19-year-old Krysta Michelle Tsukahara and 20-year-old Jack Nelson survived the initial collision on November 27, 2024, but could not escape because the Cybertruck’s power-dependent interior door buttons stopped working and the manual mechanical overrides were too obscure to find amid darkness, smoke and panic. A third passenger, 19-year-old driver Soren Dixon, also died at the scene; a fourth occupant was pulled from the truck by a friend following behind. Tesla has not commented on the lawsuits.

According to the complaints and corroborating local reports, the Cybertruck struck a retaining wall and a tree just after 3 a.m. in the Oakland suburb before catching fire. Tsukahara, a Savannah College of Art and Design student home for Thanksgiving break, and Nelson, a former Piedmont High School classmate, were riding in the rear seat. Both families argue the truck’s door design—relying on electronic releases with concealed mechanical backups—left their children without an accessible escape path when the low-voltage system failed after impact. Each suit also names Dixon’s estate and the truck’s owner as defendants.

An amended complaint filed by Tsukahara’s parents asserts she “survived the collision with no life-threatening injuries but couldn’t get out after the Cybertruck caught fire due to the vehicle’s complex electronic door mechanisms.” Her father, Carl Tsukahara, said in a statement released through family counsel: “Krysta was a bright, kind, and accomplished young woman with her whole life ahead of her… This company is worth a trillion dollars—how can you release a machine that’s not safe in so many ways?” Family attorney Roger Dreyer called the case “about truth and accountability,” alleging “there was no functioning, accessible manual override or emergency release for her to escape.” The complaint says she died of smoke inhalation and thermal injuries.

Nelson’s family filed a parallel action that likewise centers on alleged door failures in the seconds after the crash. Their suit contends that “due to electronic failures, Nelson was unable to exit the truck,” arguing the Cybertruck “lacked external mechanical handles” and that the interior mechanical release was too difficult to locate in the chaos. People magazine, which reviewed the filings, reported the family’s assertion that Nelson’s death was caused by smoke inhalation and burns rather than blunt-force trauma.

The California Highway Patrol’s post-crash findings, cited in multiple accounts, place the Cybertruck at high speed and say the teenage driver was impaired. Press summaries of toxicology results referenced by the families’ lawyers indicate alcohol and narcotics in the driver’s system; the Tsukahara complaint also targets Dixon’s estate for negligence. Only one passenger survived after a bystander broke a window and pulled the occupant clear, according to local coverage compiled around the lawsuits.

In the wake of the filings, national wire services framed the cases inside a broader safety debate about power-reliant doors on modern Teslas. The Associated Press noted that federal safety regulators opened a preliminary evaluation in September into reports of inoperable exterior door releases in certain Tesla models during low-voltage failures—a separate issue from the Piedmont crash but one that similarly raises questions about redundancy and emergency access when power is disrupted. Regulators said they would assess “the approach used by Tesla to supply power to the door locks and the reliability of the applicable power supplies.” Tesla did not respond to AP’s request for comment on the lawsuits.

Owner documentation for the Cybertruck shows Tesla’s intended escape paths when the truck loses 12-volt power. The company’s online manual instructs occupants to “use manual door releases” if the vehicle has no power, specifying for the front doors that the mechanical pull is located “in front of the window switches.” For rear doors, the Cybertruck manual directs occupants to remove the rubber mat from the rear door’s map pocket and pull up a concealed mechanical latch or cable before pushing the door open—steps that require familiarity in advance. The door’s exterior opening is by electronic button on the pillar; there are no traditional exterior mechanical handles to pull.

Family lawyers argue that, whatever the written instructions, real-world access in a post-impact, smoke-filled cabin at night is another matter—particularly for rear-seat passengers unfamiliar with the truck. Critics have long warned that door designs which require power for normal operation and training to use manual overrides risk confusion in emergencies. A 2024 owner-manual update and service guides place the rear emergency release behind trim in the door pocket area; Cybertruck owner forums and consumer explainers published before the lawsuits similarly urged drivers to brief passengers on the location of the hidden releases.

The Piedmont crash has revived comparisons to earlier litigation over Tesla door systems. In Florida, the family of Dr. Omar Awan alleged that retractable exterior handles on a 2016 Model S failed to deploy after a 2019 crash and fire, blocking rescuers; Awan died of smoke inhalation. That case focused on a different model and mechanism—motorized flush handles that present when powered—but it crystallized concerns about reliance on electronics for egress and access. Coverage of that lawsuit and related filings documented first responders’ difficulties getting doors open as fire grew, though Tesla disputed the claims and cited the driver’s speed and blood-alcohol level.

Investigators have not publicly attributed the Piedmont deaths to any single factor beyond the crash and subsequent fire, and the lawsuits’ design-defect allegations will be tested in court. The families say their children were alive after impact and that the failure to exit transformed survivable injuries into fatal smoke inhalation. Tesla has previously emphasized in manuals that every vehicle includes mechanical releases and warns owners not to use them while moving, but plaintiffs argue those releases are not reasonably discoverable under duress, especially in the rear cabin, and that the absence of external mechanical handles leaves bystanders with fewer options if power is compromised.

The AP reported that federal regulators’ preliminary probe—opened after parents complained about being unable to open rear doors from outside when voltage sagged in certain Tesla SUVs—will examine power supply architecture for door locks and whether remedies or communications are adequate. Trade publications summarizing the probe say the initial focus is the Model Y and could expand if similar failure modes are present on other models. While the evaluation does not address the Cybertruck specifically, plaintiff lawyers have pointed to the broader inquiry to argue Tesla should strengthen redundant mechanisms and public instructions across the lineup.

Details in the lawsuits and local reports outline the final minutes before the Piedmont fire overwhelmed the cabin. Friends were driving home from a night out on the eve of Thanksgiving when the truck left the road on a residential stretch of Hampton Road between Sea View and King Avenues. A companion car following behind stopped and a bystander broke glass to pull one passenger out; three others succumbed. Both families say their children would have lived had doors opened quickly. The Guardian, citing the complaints, reported that Tsukahara died from smoke inhalation and burns, not crash trauma, and that Nelson’s parents make the same assertion.

The families’ legal strategy seeks damages and, by implication, design changes. Attorneys have highlighted that Tesla has long marketed its vehicles’ safety credentials and argue that emergency egress should not depend on hidden steps. In parallel with the suits, consumer explainers and owner forums have circulated extracts of Tesla’s instructions on manual releases and advised giving every new passenger a “safety briefing” similar to airline practice—a suggestion advocates say underscores the point that the current setup is not intuitive in a crisis.

People familiar with the truck’s interior layout say the front-door manual pull is a small lever integrated ahead of the window switches, a location that can be missed by first-time riders accustomed to conventional mechanical handles. For rear passengers, the need to remove pocket lining to reach a cable or latch makes the operation more involved, and plaintiffs argue that any solution requiring multiple fine-motor steps in thick smoke is inherently unsafe. Tesla’s cautionary notes that manual releases are “for use only when Cybertruck has no power” reflect another trade-off: frequent use risks trim damage, so many owners never practice the motion that could save seconds in an emergency.

The lawsuits arrive at a sensitive moment for Tesla’s engineering choices around doors and latches. A recent preliminary evaluation by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration flagged exterior inoperability during low-voltage events in other Teslas, and business press has reported the company is exploring revisions to improve “fail-safe” behavior and human factors—claims Tesla has not publicly detailed. Safety analysts note that many automakers default to mechanical redundancy for primary egress, with electronics layered on top; Tesla’s approach, which leans on electronic actuation with concealed mechanical fallbacks, places heavier weight on documentation and user familiarity.

What is uncontested is the loss and the identities. Tsukahara’s parents describe a high-achieving student eager to return to art school; Nelson’s relatives say he was asphyxiated when he could not get out. A community still reeling from the Thanksgiving-week crash has watched as the cases move from grief to docket. The families say they want answers beyond individual blame: why, they ask, did a modern truck without power leave rear-seat teenagers searching for a hidden latch while smoke rose around them? Tesla has not answered that question in public, and the company did not respond to requests for comment reported by national and local outlets after the filings.

Legal proceedings will play out in Alameda County Superior Court. The plaintiffs are expected to seek discovery on design decisions for the Cybertruck’s door system and on any internal analyses of door operability during and after low-voltage failures or high-g crashes. They may also probe whether Tesla considered adding more obvious mechanical overrides—particularly for rear doors—or exterior mechanical access points usable by rescuers with gloves and limited visibility. For now, both sides are silent outside filings; a court schedule has not yet been set publicly.

For regulators, the Piedmont crash amplifies a narrower but related question already under federal review: what happens to door operability when a Tesla’s low-voltage system drops out, and are users sufficiently equipped—by design or instruction—to open doors quickly from inside and outside? The Office of Defects Investigation says it is assessing scope, severity and the reliability of power supplies serving locks and latches, along with the adequacy of company communications to owners. Any further action from Washington could influence the legal cases by establishing a safety baseline or identifying remedies that plaintiffs say were overdue.

Pending those outcomes, attorneys and safety advocates have urged owners to brief passengers on the location of the manual releases and to carry simple window-breaking tools, noting that laminated side glass on some modern vehicles can complicate emergency access. Tesla’s own materials emphasize the presence of mechanical releases and the need to use them only when power is absent; families in Piedmont say that in the only moment that mattered, those releases weren’t findable fast enough. Their suits contend that a reasonable design would default to obvious, mechanical egress paths in the dark, with electronics adding convenience rather than gating escape. The coming months will test whether a court agrees.