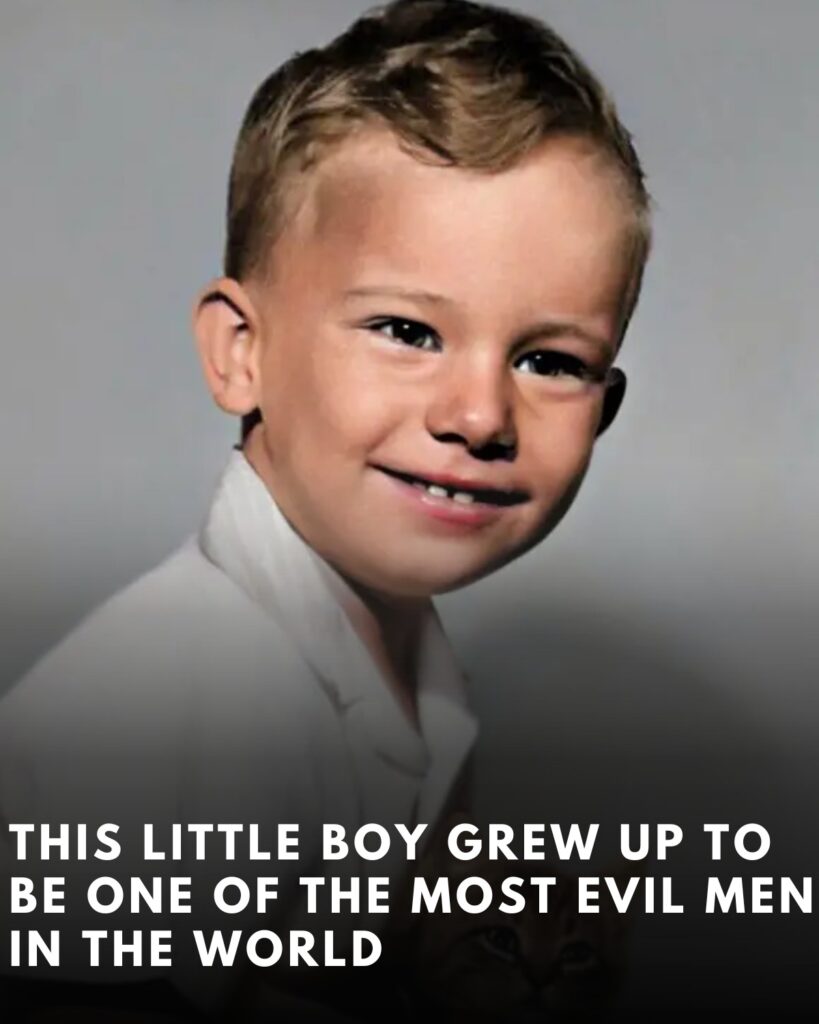

A childhood photograph of Jeffrey Dahmer has been circulating widely on social platforms, prompting another wave of online fascination and debate about how images from a killer’s early life are framed and consumed. The picture—shared in recent days in reposts on X with the caption, “A photo of Jeffrey Dahmer when he was a kid,” and in earlier threads on Reddit and other feeds—shows a boy identified as Dahmer years before the murders that later made him infamous. The renewed attention follows multiple widely viewed posts on X from history-and-fact accounts that resurfaced the image with minimal context, drawing tens of thousands of views and a stream of comments in which users alternated between calling the portrait “ordinary” and projecting ominous meaning onto it in hindsight. In one instance, the picture was published with the brief line “A photo of Jeffrey Dahmer when he was a kid,” a minimal caption that left interpretation to the replies; another account posted a near-identical line alongside the same image, helping to push it back into trending territory.

Beyond the basic portrait, a separate childhood shot that has circulated for months depicts a youngster identified as Dahmer dressed for Halloween in a T-shirt featuring a devil graphic, an archival-style photograph that repeatedly reappears on Reddit’s history and nostalgia forums. That seasonal image, which commenters often frame as eerie when viewed through the lens of later events, has been re-shared in cycles—especially around late October—by accounts that curate historical ephemera. The two threads of circulation—a plain childhood portrait and the Halloween snapshot—have together fed the latest spike in attention, with users juxtaposing “ordinary kid” language under the former and darker inferences under the latter. Even in those comment sections, posters frequently note that nothing in the pictures constitutes evidence of future crimes; the photographs persist online largely because people continue to look for clues that are not, in fact, visible.

The fresh round of sharing is the latest example of how a single asset—here, a simple childhood picture—can move across platforms with small caption tweaks and accumulate reach as it goes. On X, the most recent shares have collected views in the tens of thousands in short order, as measured on the platform’s public counters; one history-themed account’s version of the post last year also drew traction, illustrating how little is required to reanimate interest in long-known material. That limited framing has become standard for true-crime-adjacent content, where images are often posted without extended sourcing or provenance and left to audience interpretation. In this case, the viral caption offered no more than the identification of the child as Dahmer and allowed the replies to do the interpretive work, an approach that produced the familiar split between those who cautioned against mythologising and those who insisted that menace could be glimpsed in a child’s face only because of what is known now.

As the image bounced around feeds, some users contrasted the portrait with Dahmer’s well-documented high-school years, where he has been photographed with classmates and appears in club pictures that later became part of his legend. Those photographs have their own, separate online life: forum posts and social snippets periodically cite accounts from former classmates that Dahmer would “prank” yearbook photographers by slipping into group shots, anecdotes that were repeated in fan-curated true-crime spaces long before the current Netflix era. The latest circulation of the childhood image has revived that cluster of memories in comments, with people resurfacing the well-known claims that his face was blacked out in certain club photos by exasperated staff—stories that, like the images themselves, tend to be recounted as lore with varying degrees of sourcing but are repeatedly attached to the same handful of scanned yearbook pages.

The renewed interest also arrives against a durable cultural backdrop that has kept Dahmer near the surface of the online conversation for years. Feature articles and encyclopedic entries continue to outline the facts of his life and crimes—born in 1960 in Milwaukee; the murders of 17 men and boys between 1978 and 1991; and his death in prison in 1994—details that are now familiar to many and provide the context in which any childhood picture will be read. Those summaries are often the first ports of call for users who stumble across a viral image and go searching for baseline information about the person it purports to show. In this case, readily accessible biographies and timelines again served that function, anchoring the debate in a factual frame even as the most-shared posts offered little more than a caption.

The specific provenance of the latest widely shared childhood portrait remains thin in the viral posts themselves, which provide no archival credit or family source; instead, the picture is treated as a floating artefact of a public figure’s past. That is a common pattern with images of notorious subjects whose photographs have long ago entered the digital commons, where re-uploads are detached from their original publications. Earlier community posts on Reddit have featured different family images labelled as never-before-seen or as part of private collections, claims that speak to the appetite for anything that promises a “new” angle on a person already exhaustively covered. The current wave, however, does not rely on novelty so much as on a periodic resurfacing, timed to the rhythms of social media rather than to any fresh discovery.

Audience responses this week ran along lines that have become familiar since the late-2022 boom in Dahmer content. A portion of commenters insisted that nothing in a child’s face can predict the crimes of the adult; others argued that the knowledge of what came later inevitably colours how such photos are perceived. A minority admonished posters for reviving material that, they said, risks glamorising a murderer or retraumatising families of victims. The posts themselves did not solicit reactions beyond the neutral identification; the tenor of the replies—the “looks like any kid” contingent versus those who claimed to see “coldness”—was shaped by the minimalism of the caption and by the underlying fascination with origin stories in true-crime culture.

Several commenters cross-referenced Dahmer’s childhood home and high-school years, touchpoints that tend to surface when early-life images circulate. The detached ranch house in Bath, Ohio, where he lived as a teenager, has drawn attention in journalism and film—most notably in the 2017 feature My Friend Dahmer, which dramatised his adolescent years and filmed at or recreated elements of the real locations. That film, based on a graphic novel by a former classmate, is not referenced in the viral posts, but users often mention it in comment threads as cultural context when childhood or teenage pictures appear. The latest re-sharing of the portrait produced the same effect: people invoked the film as a reason they felt they “knew” the boy in the picture, even when the image itself carried no cinematic tie.

The dynamic at play—an old image, a new spike in engagement, and a shell of a caption—matches the typical lifecycle of viral true-crime artefacts. In this instance, the mechanics were visible: one account posts a plainly labelled picture; another copies the framework days or weeks later; both sets of replies refill with speculation or pushback; and the image is then exported to other platforms, including Instagram reels that compile “before they were infamous” portraits. The feedback loop persists because the inputs are minimal and reproducible, and because the photographs themselves are frictionless: a face at a particular age, detached from narrative except for the viewer’s own.

The picture’s return to public view also rekindled a broader conversation about the responsibilities of accounts that trade in historical or “fascinating” images. Some users asked posters to include links to basic biographies or verified timelines when publishing material tied to violent figures; others argued that context inevitably blunts the shareability that drives such accounts’ growth. While those debates rarely change posting behaviour, they appear under nearly every resurfaced Dahmer image—especially the childhood snapshots—because they sit at the intersection of curiosity, caution and the commodification of a face that pre-dates any crime. The most recent X posts did not add context beyond identification; the replies did that work themselves, often pointing latecomers to standard biographical resources.

All of this unfolds in an online environment still saturated with Dahmer content following 2022’s streaming surge, which reintroduced the case to a new generation and seeded countless derivative posts. The current viral childhood image is not new in any documentary sense; it is simply newly visible again, travelling on the momentum of high-follower curation accounts whose formula is to present striking or historically resonant images with spare captions. In that sense, the photograph’s latest moment is less a discovery than a reminder of how social platforms repackage the past on a loop, each time allowing viewers to supply the meaning.

What can be stated with confidence, based on the publicly available posts, is narrow but clear: an image identified as showing Jeffrey Dahmer as a boy has been re-shared widely on X with captions that say only that it is a childhood picture; an older Halloween-costume photograph of a child labelled as Dahmer has simultaneously recirculated in Reddit and Instagram history feeds; and the replies under those posts show the now-familiar split between those who see an ordinary school-age face and those who overlay it with foreknowledge of the crimes that would come decades later. The posts themselves do not assert new claims about cause or psychology, nor do they present new archival information; they present an image and a name and leave the rest to the audience. In the absence of fresh reporting about the photograph’s origin, verification rests on the surface-level presentation by accounts that treat the picture as part of the public domain of Dahmer-related material, a status it has effectively held for years by virtue of repeated circulation.

For readers seeking context beyond the feeds, the underlying facts remain those laid out in reliable reference sources: Dahmer murdered 17 men and boys between 1978 and 1991, was arrested in July 1991, convicted and sentenced to multiple life terms, and was killed in prison in 1994. He grew up in Wisconsin and Ohio, with biographical accounts noting family upheaval and increasingly disturbing adolescent behaviours that escalated in adulthood into the crimes for which he is known. Those facts do not—and cannot—turn a childhood photograph into evidence of anything; they are the backdrop against which the image is inevitably judged. The reaction to this week’s circulation shows how persistently people return to early-life pictures in search of answers that photographs cannot supply, and how reliably those pictures will be reposted whenever the algorithm rewards a familiar face with a familiar caption.

Viewed strictly as a media moment, the surge around the childhood portrait offers a tidy case study in how true-crime images are made viral. A minimal caption; an instantly recognisable name; a neutral photograph that invites projection; a comments section that supplies both scepticism and sensation; and a second, thematic image—the Halloween T-shirt—that gives the cycle seasonal hooks. Nothing in the posts suggests new evidence or fresh discovery; the novelty lies in the timing and in the audience’s willingness to look again. For as long as that appetite endures, photographs like these will continue to move, accruing views not because they change what we know, but because they ask viewers to reconcile an ordinary child’s face with extraordinary crimes, and because social platforms are designed to reward that irresolvable tension with reach.