Cyd Charisse could do it all—sing, act, and dance like music made flesh. Those impossibly long legs became legend, but she began as Tula Ellice Finklea, a sickly Texas girl recovering from polio. Ballet, meant to build her up, gave her a life. A brother’s mispronounced “Sis” became “Cyd,” and Hollywood did the rest.

She grew up in Amarillo, where wind and dust outnumbered spotlights. Ballet remade her body, and by her teens she was studying in Los Angeles and abroad. Briefly she used Russian-sounding names, but the essence remained: cool elegance, fierce musicality.

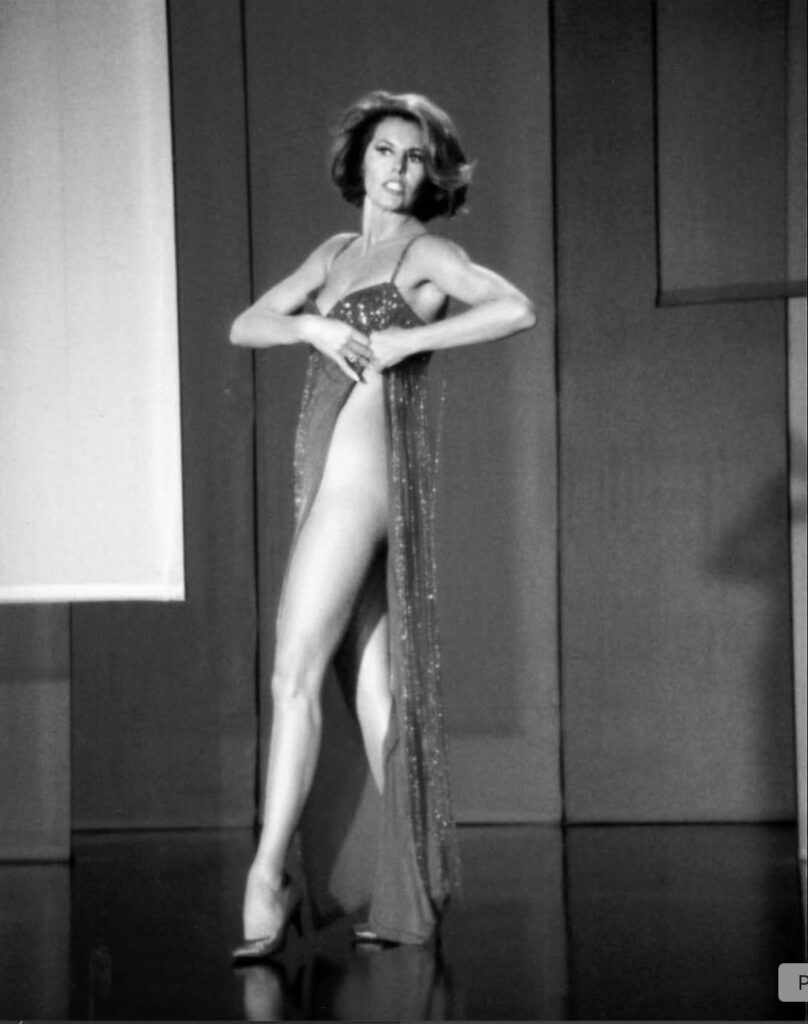

Film found her through dance, not dialogue. MGM signed her in its golden era, letting her ripen from uncredited roles to the dazzling “Broadway Melody” ballet in Singin’ in the Rain (1952). In a green dress, with endless legs, she spoke volumes without a line.

Rare among dancers, Charisse shone with both Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire. With Kelly she was silk-covered steel; with Astaire she breathed phrasing into every step. In The Band Wagon (1953), their “Dancing in the Dark” is pure inevitability—two people waltzing into eternity.

Her genius wasn’t just legs, but phrasing. Ballet training gave her line and carriage, but she made jazz and modern shapes feel inevitable. Where others sold speed, Charisse sold time—stretching, suspending, then snapping it like silk.

MGM kept her busy: the danger of Singin’ in the Rain, the sophistication of The Band Wagon, the wit of Silk Stockings(1957), the allure of Party Girl (1958). Offscreen she was punctual, private, and devoted to singer Tony Martin, her husband of six decades.

Tragedy touched her life when her daughter-in-law died in the 1979 Flight 191 crash. Yet Charisse endured with quiet grace, later returning to the stage and mentoring dancers. In 2006 she received the National Medal of Arts.

She died in 2008, but her films still hum. Watch The Band Wagon and feel the park turn to ballroom. Cue Singin’ in the Rain and see the green dress burn into memory. Her language was movement. Her legacy still dances.