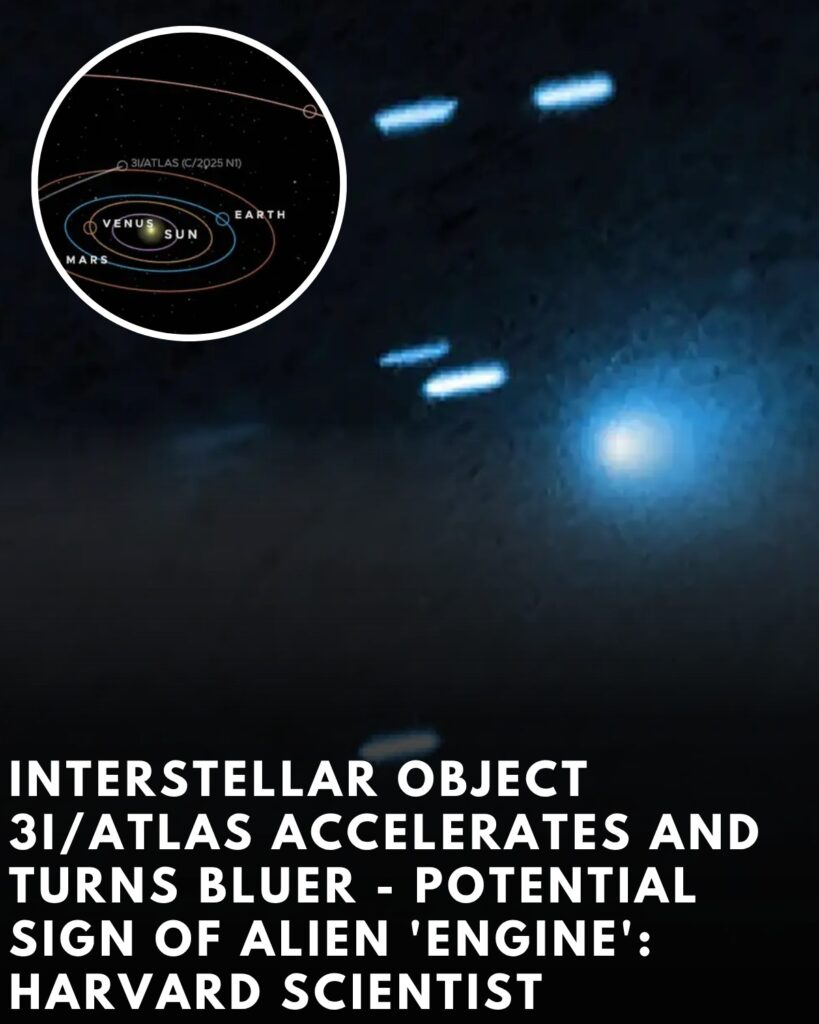

Astronomers tracking the interstellar visitor 3I/ATLAS say the object brightened far more rapidly than expected as it swung past the Sun on 29 October and appeared “distinctly bluer than the Sun,” behaviour they attribute to strong gas emission captured by space-based cameras while the comet was hidden from Earth’s ground telescopes by solar glare. In an analysis posted to the arXiv preprint server, Qicheng Zhang of Lowell Observatory and Karl Battams of the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory reported that images from multiple heliophysics spacecraft showed 3I/ATLAS’s brightness scaling roughly as the inverse heliocentric distance to the power of 7.5 in September and October, a surge that outpaced typical long-period comets and coincided with a colour shift they measured in LASCO data from the SOHO observatory. “LASCO color photometry shows the comet to be distinctly bluer than the Sun, consistent with gas emission contributing a substantial fraction of the visible brightness near perihelion,” they wrote, adding that GOES-19 imagery resolved an extended coma several arcminutes across. Their dataset relied on coronagraphs and heliospheric imagers aboard STEREO-A, SOHO and GOES-19—platforms that could see the interstellar object when its position near the Sun put it beyond reach of most observatories on Earth.

The unusual brightening and colour change have revived debate about how interstellar comets behave under solar heating and how to distinguish exotic physics from ordinary, if vigorous, outgassing. In a series of commentaries, Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb argued that a separate, newly claimed detection of non-gravitational acceleration at perihelion—an apparent small push on the object beyond what gravity alone would provide—deserves urgent scrutiny, noting that such accelerations are often produced naturally when jets of volatile gas erupt from a comet’s surface but could, in principle, have other explanations. He characterised perihelion as an “acid test,” writing that sustained solar heating should either drive visible fragmentation and a massive gas plume if 3I/ATLAS is a loosely bound natural body, or else produce signatures inconsistent with normal cometary physics. In a subsequent post titled “First evidence for a non-gravitational acceleration of 3I/ATLAS at perihelion,” Loeb listed radial and transverse acceleration components and urged that the underlying measurements be released in full so the community can attempt independent verification. “A request for NASA to release scientific data on 3I/ATLAS” followed, in which he pressed for prompt access to astrometry and imaging that would allow teams to test whether the putative acceleration can be explained by outgassing alone.

Mainstream space-science outlets summarising the arXiv analysis and related observations have focused on what can be stated with confidence: 3I/ATLAS passed perihelion at about 1.36 astronomical units (roughly 203 million kilometres) from the Sun; spacecraft photometry indicates an unusually steep brightening trend; and colour measurements near closest approach are best explained by strong gaseous emission dominating the reflected light, hence the blue tint. Space.com reported that the rapid brightening “remains unclear” in origin and “far exceeds” the rate seen in typical Oort-cloud comets at similar distances, while Sky & Telescope told amateur observers to expect the interstellar object to emerge from conjunction brighter than when it disappeared in early October, with ground-based prospects improving in December if activity continues. Those reports echoed Zhang and Battams’s conclusion that activity intensified in the weeks before perihelion and that gas emission played a major role in the visible output.

Separate context has emerged from longer-baseline studies of the object’s surface chemistry under interstellar radiation. A recent write-up of James Webb Space Telescope results said 3I/ATLAS’s outer layers appear to have been altered over billions of years by galactic cosmic rays, forming a carbon-dioxide-rich crust tens of metres deep as carbon monoxide was converted to CO₂—findings that imply what telescopes see today may be heavily processed material rather than pristine ice from the comet’s birth environment. Researchers hope continued solar erosion could strip away some of this irradiated shell as the comet recedes, potentially exposing less altered material and offering a cleaner window into the object’s origins. The same report noted preliminary age estimates on the order of seven billion years, underscoring how unusual it is to witness such ancient matter passing through the inner solar system.

The claims about non-gravitational acceleration—strongly associated in public discussion with Loeb due to his essays and interviews—sit in a grey zone pending broader data release. In his own back-of-the-envelope analysis, Loeb suggested that if the reported acceleration near perihelion was entirely due to cometary jets, momentum conservation would imply substantial mass loss over a period of weeks. He contrasted that estimate with JWST-derived mass-loss rates earlier in the year, which he said did not yield a detectable non-gravitational push before October, and predicted that if jets were indeed responsible for the perihelion kick then a “massive cloud of gas” should become obvious in November and December. He has also framed the blue colour as surprising in its strength because dust typically reddens scattered sunlight, although the arXiv authors’ interpretation is that prominent gas emission, not dust, dominated the visible brightness near perihelion, aligning with the colour measurement. Once the relevant astrometry is widely available, comet dynamicists are likely to fit activity models to the trajectory to test whether outgassing at plausible orientations and rates can reproduce the observed motion.

What is not in dispute is that 3I/ATLAS is only the third interstellar object confirmed passing through the solar system—after 1I/‘Oumuamua in 2017 and 2I/Borisov in 2019—and that its geometry this autumn complicated ordinary observing. Because the comet approached perihelion essentially on the far side of the Sun as seen from Earth, the best data during the crucial weeks came from solar-viewing spacecraft rather than ground-based telescopes. Zhang and Battams emphasised that gap in their paper and used the vantage points of STEREO-A’s SECCHI imagers, SOHO’s LASCO and GOES-19’s CCOR-1 to build a continuous light curve through conjunction. With the object now moving away from the Sun’s glare, professional and advanced amateur facilities are preparing to reacquire it in December, when any sustained activity or evolving colour could test interpretations offered in the early analyses.

Public interest has spiked in part because the behaviour tracks two of the most contentious aspects of 1I/‘Oumuamua’s story—colour and non-gravitational acceleration—without being an exact replay. ‘Oumuamua’s anomalous acceleration ignited years of debate over whether exotic natural processes, such as outgassing of difficult-to-detect volatiles or radiation pressure acting on an unusually thin body, could explain the small push measured by precision astrometry. In the present case, the blue tint and steep brightening of 3I/ATLAS have a straightforward astrophysical explanation in gas emission at perihelion temperature, according to the arXiv work; the outstanding question, should a perihelion acceleration be confirmed at high significance, is whether the magnitude and direction of that push align with a jetting model constrained by photometry and any forthcoming spectroscopy. Loeb has said he is keeping alternative hypotheses on the table until the data are exhaustively tested, writing that the “appearance of 3I/ATLAS as bluer than the Sun is very surprising” and reiterating that full, prompt data release is the best antidote to speculation.

Amid the debate, practical planning continues for how best to seize the next observing window. A technical preprint circulated in August mapped opportunities for spacecraft assets—from NASA’s Psyche probe to the fleet around Mars and ESA’s JUICE mission—to attempt opportunistic observations during periods of favourable geometry, arguing there is “a strong science case” for coordinated campaigns as the object recedes. Ground-based teams, including survey facilities that helped piece together the discovery arc in July, are preparing to resume tracking once elongation improves, with early-December reacquisition windows highlighted in popular astronomy briefings. A Kolkata science museum even scheduled an outreach day to coincide with the perihelion passage, emphasising how rarely interstellar visitors offer such a close-range laboratory for gas and dust physics.

Scientists caution that colour alone cannot adjudicate exotic claims. Gas-rich comae can appear blue in broad filters when emission bands contribute more to the detected light than the solar continuum reflected by dust, and strong gas emission near perihelion is consistent with an interstellar body with abundant volatiles that were locked up during a long, cold journey through deep space. The arXiv study’s reported r^-7.5 brightening index is steep but not impossible if activity surged due to increased solar heating; the surprise is the rate of change compared with many comets observed at similar distances. If subsequent ground observations find that the blue tint fades as the comet cools and that its light curve returns to more ordinary behaviour, the perihelion episode may be filed under “vigorous but natural.” If, on the other hand, precise post-perihelion astrometry confirms a statistically robust acceleration that cannot be reconciled with plausible jet models, the discussion will shift to less familiar territory. For now, the most conservative reading is that 3I/ATLAS behaved like a highly active comet as it rounded the Sun, and that only the full release of position measurements and imaging will show whether anything more exotic occurred.

Loeb’s advocacy has ensured that questions about transparency remain in the foreground. In his “request for NASA to release scientific data,” he framed rapid, open dissemination as a way to let the evidence speak before speculation hardens into certainty online. He has also noted that some of the most useful vantage points during conjunction were held by U.S. government-operated spacecraft, further strengthening the case for coordinated, public data drops now that the critical weeks around perihelion have passed. While popular outlets have amplified his more provocative hypotheticals—including whether non-gravitational forces could ever be consistent with propulsion—the astrophysicist has repeatedly acknowledged that robust natural mechanisms exist and that outgassing is the leading candidate pending analysis. That distinction—between raising a question and asserting a conclusion—will likely be important as new datasets arrive and teams publish modelling of the object’s motion and coma physics.

As 3I/ATLAS emerges from the Sun’s neighbourhood into darker skies in December, observatories will try to answer three immediate questions. First, does the object remain unusually blue, implying sustained gas emission, or does its colour revert as activity wanes? Second, is there spectroscopic evidence that isolates specific gaseous species driving the perihelion glow, beyond the broad-band colour in coronagraph data? Third, do precise position measurements, once corrected for observational biases near the Sun, show a residual acceleration that persists or that can be convincingly modelled by jets? The answers will determine whether the interstellar visitor’s perihelion passage joins the catalogue of cometary extremes or stands apart as something that demands a new category. For now, the public record supports a restrained summary: the third confirmed interstellar object brightened sharply and turned bluer as it rounded the Sun, behaviour best explained by gas emission; a Harvard scientist has publicised a claimed perihelion acceleration and called for immediate data release to test whether vigorous outgassing is enough to account for it; and the next six weeks of observations will likely decide which interpretation holds.