Lee Tamahori, the New Zealand filmmaker who directed the 2002 James Bond instalment Die Another Day and the landmark drama Once Were Warriors, has died at the age of 75 after living with Parkinson’s disease, his family confirmed in a statement released via New Zealand public broadcaster RNZ and carried by multiple outlets. The statement said he died peacefully at home surrounded by loved ones on 7 November.

Born in Wellington in 1950 and of Māori and British heritage, Tamahori began his career in the New Zealand screen industry in the 1970s, starting in technical roles before moving into directing commercials and then features. He broke through internationally with his 1994 debut feature Once Were Warriors, a searing portrayal of a Māori family that set box office records in New Zealand and drew wide critical attention for its uncompromising depiction of domestic violence and disenfranchisement. The film’s commercial impact at home and its festival profile abroad propelled Tamahori to sustained work in Hollywood over the following decade.

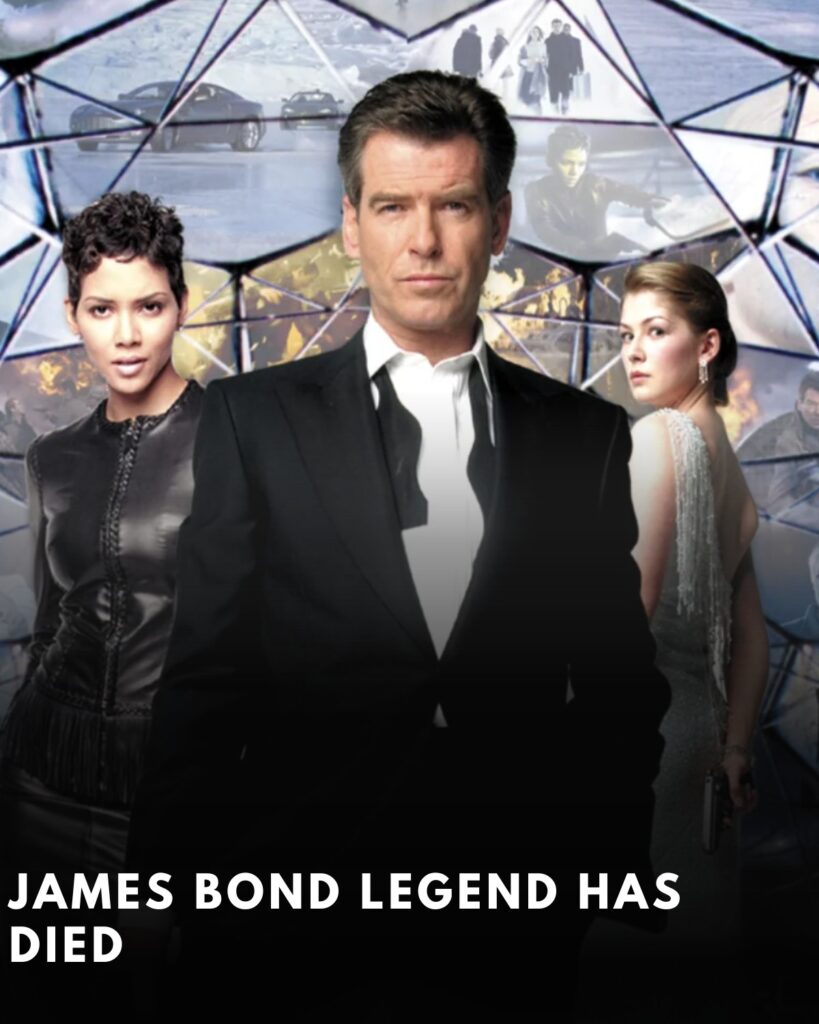

In Hollywood he assembled a string of studio projects with prominent casts, directing the 1996 noir Mulholland Falls, the 1997 wilderness thriller The Edge, the 2001 crime drama Along Came a Spider and later the Nicolas Cage-led Next in 2007. The most conspicuous assignment came in 2002 when he took over the 20th entry in Eon’s James Bond franchise, Die Another Day, the final film to star Pierce Brosnan as the 007 agent. While reviews were mixed, the film delivered strong box office returns globally and broadened Tamahori’s profile among mainstream audiences. Industry retrospectives following his death described him as a director who moved fluidly between national cinema and large-scale studio entertainment.

The family tribute released to RNZ emphasised his advocacy for Māori stories and performers and his role in developing New Zealand screen talent. “His legacy endures with his whānau, his mokopuna, every filmmaker he inspired, every boundary he broke and every story he told with his genius eye and honest heart. A charismatic leader and fierce creative spirit, Lee championed Māori talent both on and off screen,” the statement read. The words were widely quoted in coverage of his death and echoed by colleagues who credited him with opening doors for a generation of filmmakers from Aotearoa New Zealand.

Tamahori’s later career included a return to New Zealand to make Mahana (also known as The Patriarch) in 2016 and, most recently, The Convert, a 19th-century historical drama starring Guy Pearce that premiered in 2023–24. The move back toward stories grounded in local history and identity was framed by the family as a conscious turn “to tell stories grounded in whakapapa and identity,” culminating in a body of work that looped from international thrillers back to narratives rooted in Māori experience and New Zealand settings.

As news of his death spread, appreciations focused on the scale of the impact of Once Were Warriors, which remains a touchstone of New Zealand cinema for its raw, unvarnished treatment of poverty and violence and for performances that helped propel actors including Temuera Morrison and Rena Owen to wider renown. The film’s success created opportunities for Tamahori to work with major studios, but also etched a stylistic reputation for muscular, propulsive storytelling that he carried into his American projects. Subsequent films like The Edge and The Devil’s Double were frequently cited by colleagues as evidence of his versatility across genres, from survival drama to political thriller.

Die Another Day, released to mark the 40th anniversary of the Bond franchise, brought Tamahori into one of cinema’s most closely watched directing roles. The film combined traditional 007 motifs with early-2000s digital effects and stunts on an expansive scale, and later served as a pivot point for the series as producers moved to a different register with the Daniel Craig era. Tamahori’s Bond entry, though sometimes contested critically, was a commercial success and remains the capstone of Pierce Brosnan’s tenure, embedding the New Zealand director’s name permanently within the franchise’s long history. Industry sites devoted to Bond commemorated Tamahori as a figure who left a distinctive mark on the series and as a director remembered fondly by collaborators.

Outside the franchise, Tamahori’s American studio period placed him alongside leading actors of the time. Mulholland Falls featured Nick Nolte and John Malkovich, The Edge paired Anthony Hopkins with Alec Baldwin, and Along Came a Spider continued a cycle of adaptations from James Patterson’s Alex Cross novels. The varied slate reflected a pragmatic approach Tamahori often described in interviews, positioning himself as a craftsman focused on story propulsion over auteurist signatures. Colleagues recalled that orientation as central to his on-set manner, with a production style that prized pace and clarity.

Tributes following his death underscored a career that was both outward-facing and home-rooted, moving between Los Angeles and Auckland over three decades. The family statement highlighted that he ultimately “returned home to tell stories grounded in whakapapa and identity,” a sentiment reinforced by his recent films and by the crews and actors he continued to mentor in New Zealand. Industry observers noted that The Convert, which dramatises conflict between Māori iwi in the 19th century and the arrival of a British lay preacher, marked a late-career consolidation of themes that had animated his earliest works: cultural identity, violence, and the collision of worlds.

Tamahori’s death followed a period in which he had spoken publicly about Parkinson’s disease, a degenerative condition that affects movement and can impair speech and other functions. Family members said he was cared for at home and that they were present when he died. Coverage in New Zealand and abroad framed his passing as a loss not only to national cinema but to an international cohort of filmmakers who came of age in the 1990s and early 2000s. Accounts emphasised his influence on crews and apprentices, many of whom moved from commercial production into features under his supervision or example.

He is survived by his long-time partner Justine, his children Sam, Max, Meka and Tané, daughters-in-law Casey and Meri, and a granddaughter, according to statements attributed to the family. Plans for memorial observances were being organised in Auckland, with industry figures in Wellington and abroad also expected to pay respects. International media carried the family’s words in full, and the statement’s Māori terms were left intact in most reproductions, a small but notable detail that several New Zealand commentators said reflected both the family’s wishes and the cultural frame through which Tamahori understood his work.

In the years since his emergence, Tamahori’s career invited debate for choices that ranged widely across genre and budget, but the through-line colleagues most frequently cited was his attention to performance and rhythm. Actors who worked with him on Once Were Warriors credited him with creating a set where emotionally difficult material could be handled with discipline and focus; crew who joined him on large action films described a director who embraced the logistical complexity of second-unit stunts and visual effects while insisting that tempo and narrative stakes drive the set pieces. Retrospectives following his death coalesced around that dual capacity: a director equally at home staging intimate domestic violence scenes and orchestrating ice-palace chases for a global franchise.

Observers of New Zealand cinema positioned Tamahori among a generation that pushed the country’s screen profile to the world stage in the 1990s, alongside filmmakers working across independent and studio systems. Once Were Warriors’ impact, in particular, was cited as both cultural mirror and catalyst, its success paving the way for subsequent Māori-led narratives in film and television. Later projects such as Mahana and The Convert were read by critics as a conscious return to those concerns, a late-period reaffirmation of identity that paralleled an industry back home now larger and more confident than when he left for Los Angeles.

News of his death drew remarks from film fans and Bond followers on social media who highlighted the visibility the franchise gave his name and revisited the stylistic imprint of Die Another Day in the context of the series’ evolution. Others emphasised that his legacy would be measured most of all by the first feature that announced him to the world, a film which remains a reference point for conversations about representation and violence in New Zealand. The breadth of those reactions reflected a career that traversed both blockbuster spectacle and grounded, community-rooted storytelling.

Tamahori worked across film and television over his decades in the industry, and his credits included occasional work in American series as well as commercials and shorts at the outset of his career. He co-founded the production company Flying Fish in the 1980s, part of a wave of commercial production that supported the country’s developing screen workforce. Peers described that period as formative for a cadre of crew members who later staffed New Zealand and international shoots, citing Tamahori’s example as a bridge between ad-world craft and feature filmmaking. His trajectory from boom operator to director became a commonplace reference in local training programmes to illustrate pathways into the industry.

His final years were marked by continued creative activity despite illness, including promotional responsibilities for The Convert and development on other projects. International reporting this week noted that an additional production, Emperor, had encountered legal complications and remained unfinished, but that his most recent completed work reaffirmed his longstanding interest in stories set in Aotearoa. Colleagues said the persistence of that focus, from Once Were Warriors through The Convert, would shape how his career is remembered: as the record of a director who moved abroad and then returned, who worked within one of cinema’s most durable franchises and also within local historical drama, and who insisted that both undertakings could be approached with the same attention to momentum and character.

In their statement, Tamahori’s family set out the core of that legacy in terms that resonated across memorials and tributes: a filmmaker whose achievements will live on through whānau and collaborators as much as through the films themselves. Those who worked with him said privately that the measure of his influence would extend beyond credits and grosses to the skills and confidence he helped cultivate in others. With his death, New Zealand loses a figure whose career crossed borders and scales while remaining rooted in a particular cultural vantage point, and the international industry loses a director whose projects left distinct marks on the genres he entered, from gritty domestic drama to the longest-running action franchise in cinema. The immediate response from across New Zealand’s film community and the broader movie-going public suggested that his work will continue to be discussed in both lights — as national landmark and global entertainment — for years to come.

Tamahori’s survivors asked that attention in the days ahead focus on the body of work he leaves behind and on the communities that shaped and sustained him. As the industry in Aotearoa reflects on that record and international audiences revisit the films, the outlines of that legacy are already clear: a storyteller and craftsman whose films connected New Zealand to the world and whose name will remain linked to both a movement-defining local drama and an entry in one of cinema’s most recognisable series.