Health authorities in India have stepped up surveillance and contact tracing after two suspected cases of Nipah virus were reported in West Bengal, prompting the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) to say it is monitoring the situation while assessing the risk to the UK population as very low.

According to UKHSA’s “outbreaks in India” update on Nipah, reports from India described two people in the Kolkata area whose samples initially tested positive at a local laboratory, before further testing at a national reference facility reported the results as negative. The UK agency said it was continuing to monitor developments and would update its risk assessment if the situation changed.

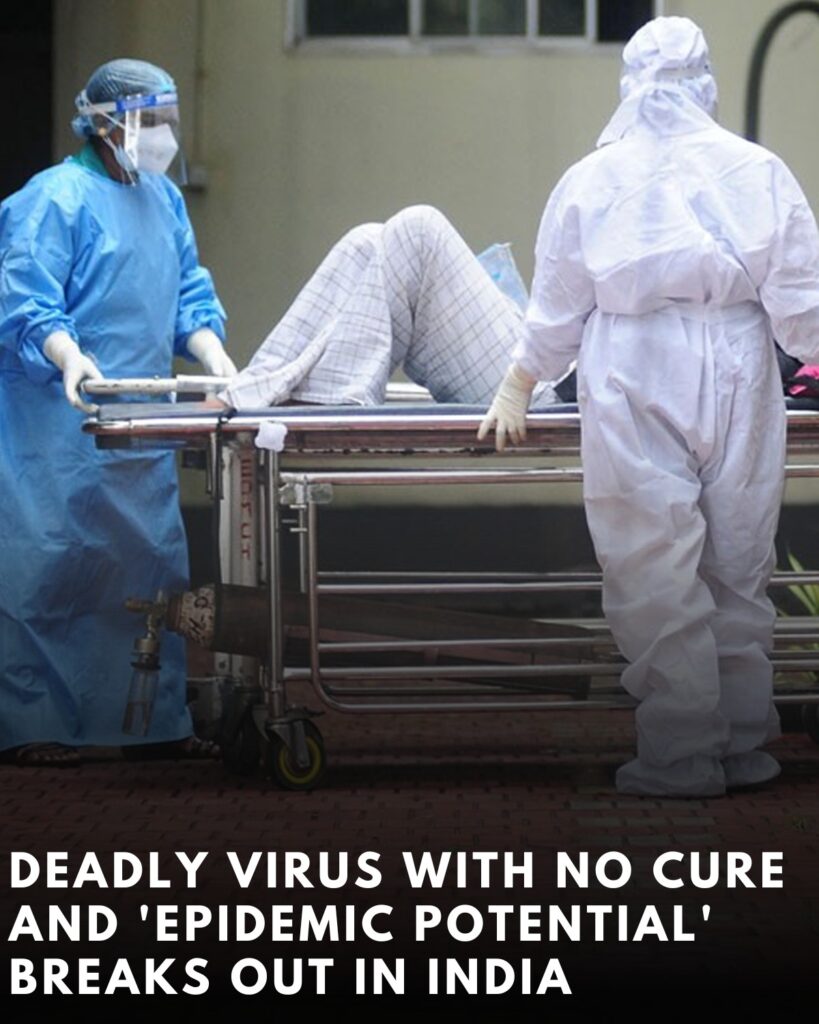

Nipah is a rare but severe zoonotic virus, meaning it can spread from animals to humans. It is known to cause illness ranging from asymptomatic infection to acute respiratory disease and encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain that can be fatal. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates the case fatality rate at between 40% and 75%, though it can vary by outbreak depending on local clinical care and surveillance capacity.

The virus is carried naturally by fruit bats of the Pteropodidae family and has historically been detected in parts of South and Southeast Asia. Human infections have been linked to direct contact with infected animals, consumption of foods contaminated by bat saliva or excreta, and, in some outbreaks, direct human-to-human transmission among family members and caregivers. WHO says there is no specific treatment or vaccine, with care focused on supportive treatment of symptoms and complications.

In its guidance for clinicians and public health officials, the UKHSA notes that human-to-human transmission has been reported in Bangladesh and India, most commonly among family members and close contacts. It says “close and direct, unprotected contact with infected patients, especially those with respiratory symptoms, has been implicated as a transmission risk”. The agency’s guidance also describes the typical incubation period as presumed to be between 4 and 21 days, while noting longer incubation periods have been observed rarely in previous outbreaks.

The suspected West Bengal incident drew heightened attention because Nipah outbreaks have previously been associated with serious illness and deaths, particularly in the southern Indian state of Kerala, which has experienced multiple outbreaks in recent years. While West Bengal has reported Nipah concerns before, confirmed outbreaks in India have been more frequently documented in Kerala, and in Bangladesh across the border, where repeated spillover events have occurred. WHO’s fact sheet states that Nipah was first recognised during an outbreak among pig farmers in Malaysia in 1999, and that subsequent outbreaks have occurred in Bangladesh since 2001, with the disease also identified periodically in eastern India.

Reports from India linked the West Bengal alert to hospitalised patients and the testing of their contacts. UKHSA’s outbreak update said the two suspected cases were connected to the Kolkata region and that authorities were monitoring contacts as a precaution, consistent with established public health practice for Nipah, given the possibility of severe disease and the historical evidence of human-to-human spread in healthcare settings during certain outbreaks.

The UKHSA guidance highlights how transmission in healthcare environments has been a feature of some past clusters, including the 2001 Siliguri outbreak in India, where a significant proportion of cases were reported among hospital staff or visitors. UKHSA also warns that, during outbreaks, contamination of surfaces in hospitals has been documented, reinforcing the need for strict infection prevention and control measures for suspected cases, including appropriate isolation and protective precautions for clinical teams.

In practical terms, the steps taken by Indian authorities typically include rapid case investigation, the isolation of suspected patients, testing through reference laboratories, and active monitoring of people who may have been exposed, particularly household contacts and healthcare staff. These measures are intended to determine whether there is a true Nipah event, and if confirmed, to limit onward transmission as early as possible.

WHO has previously highlighted the importance of prompt detection and strong health systems in limiting Nipah outbreaks. In a 2018 WHO report on the containment of a Nipah outbreak in Kerala, the organisation described how coordinated public health action, including surveillance and infection control, was central to bringing transmission under control.

Outside affected areas, UKHSA continues to characterise the risk to the UK as very low, noting that Nipah does not occur in the UK and that no travel-associated cases have been reported there. It also states that the main activities linked to infection, such as exposure to bat habitats and local practices like collecting or consuming raw date palm sap, are generally not undertaken by tourists, though risk can vary depending on activities and whether an outbreak is active in a destination area.

Health agencies emphasise that while Nipah can be severe, it does not spread in the same way as respiratory viruses that transmit efficiently through casual contact in the general community. Instead, documented human-to-human transmission has typically required close contact with bodily fluids or respiratory secretions, often in caregiving or clinical contexts.

Clinical descriptions of Nipah infection underline why suspected cases are treated cautiously. WHO says early symptoms can include fever, headache, muscle pain, vomiting and sore throat, with some patients developing respiratory illness. In more severe cases, the disease can progress to encephalitis, with neurological symptoms and, in some instances, rapid deterioration toward coma. WHO notes that encephalitis and seizures can occur in severe cases, and that some survivors may experience long-term neurological effects.

For public health systems, one of the challenges is that early symptoms are not specific to Nipah and can resemble many other infections, making rapid laboratory confirmation and careful clinical history important. UKHSA guidance notes that suspected cases in England should be discussed with infection specialists and managed by teams capable of safely treating high consequence infectious diseases, reflecting the level of caution associated with pathogens that can cause severe outcomes even if they remain rare.

The current West Bengal situation remains centred on investigation and verification of results, with UKHSA’s outbreak update indicating that follow-up testing did not confirm Nipah in the two suspected cases. Even so, health officials typically maintain vigilance, given the virus’s history and the need to rule out wider spread whenever a possible cluster is reported.